On a quiet Saturday morning in Jerusalem, visiting breathtaking St. Anne’s Church in the Old City, for just a moment, I thought I could hear the guns in Ukraine.

On a quiet Saturday morning in Jerusalem, visiting breathtaking St. Anne’s Church in the Old City, for just a moment, I thought I could hear the guns in Ukraine.

It was the sound of the authority of Jerusalem. Yesterday a friend told me about a secular-leaning visitor who’d come here wondering what the fuss was all about. After a few days, his friend said, “This really is the center of the world, isn’t it?”

St. Anne’s is an example. I’ve visited several times as a pilgrim, enjoying its fabled acoustics (hum a phrase, and it comes back sounding like Pavarotti) and the traditional notion that it’s built over the Virgin Mary’s birthplace. The first church built here, from the fifth century, straddled the pools of Bethesda, site of one of Jesus’s healings (John 5). These are now fully excavated, and visitors can explore them amply, even climbing down steep stairs into Roman cisterns.

This time, I also dug a little deeper in the church’s history. The current building, so beloved of visiting choirs, dates from the 12th century, the Crusader era. Seven centuries later, it was the spoils of war, a gift to France from the Ottoman Empire, in recognition of French support against the Russians in the Crimean War.

Yep, Crimea, once again in contention between European powers and Moscow. In the 19th century, one casus belli was the struggle between Roman Catholic and Orthodox Christians over holy sites such as the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Yet another historical road back to Jerusalem. So the French tricolor flies over St. Anne’s, whose custodians are the White Fathers, a French missionary order.

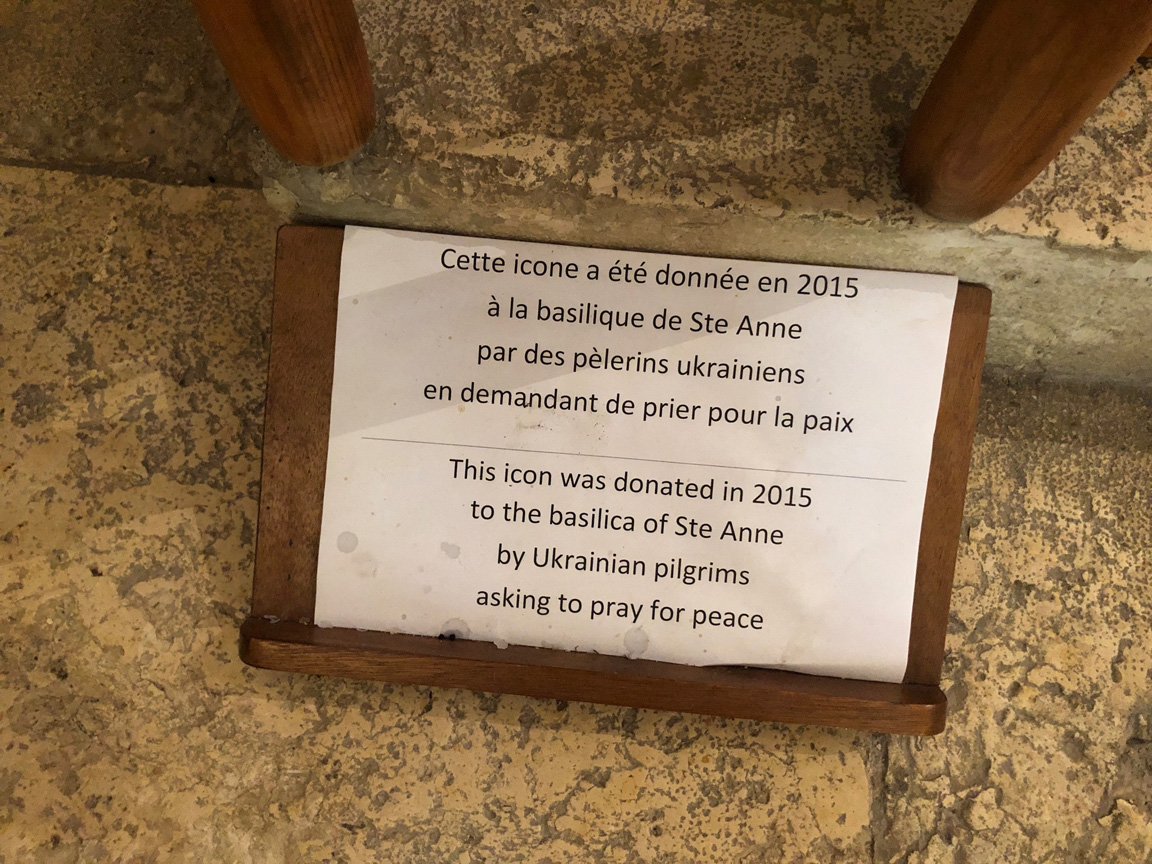

The distant thunder from Ukraine continues. Go inside, hum a few bars, and marvel at the icon of the Virgin Mary, a gift from Ukrainian pilgrims who came to Jerusalem in 2015, the year after the Russians seized Crimea. A sign posted nearby invites people to pray for Ukraine.

Again, then, St. Anne’s is at the nexus of great power struggle. The Russian Orthodox Church is all in for Putin’s ugly revanchism. Kneeling in St. Anne’s, for what shall we pray? Ukraine’s victory, including reclaiming Crimea? That would be a pretty gruesome prayer. Aggregating estimates, we can surmise that Russia may already have suffered 50,000 deaths, almost as many as the U.S. all its years in Vietnam. Tens of thousands of Ukrainians have died as well. Praying for Ukraine to prevail in such a grinding war of attrition is to pray for the loss of a quarter million souls.

Yet praying for everyone to stop fighting right now is like praying for Jesus to come back tonight; worthy but likely unavailing. Then today, at Sunday services at St. George’s Cathedral, Jerusalem, as Isaiah was read out, we actually heard the solution, if not to war, then to our prayer dilemma. The way of love, the means of peace, are and always have been in the Christlike giving up of prerogative, advantage, wealth, and self:

If you remove the yoke from among you

The pointing of the finger, the speaking of evil

If you offer your food to the hungry

And satisfy the needs of the afflicted

Then your light shall rise in the darkness

And your gloom be like the noonday. (Isaiah 58:9-10)

Maybe that is as impractical as praying for peace. And yet it is empowering to pray not for something for happen but for the grace to do something ourselves and be models for the world we want. Each of those actions is within our grasp — to stop oppressing, accusing, and slandering others and to give what we have to those who need it. We can each of us do that today, right now, wherever and however we’re living our lives.

Maybe that is as impractical as praying for peace. And yet it is empowering to pray not for something for happen but for the grace to do something ourselves and be models for the world we want. Each of those actions is within our grasp — to stop oppressing, accusing, and slandering others and to give what we have to those who need it. We can each of us do that today, right now, wherever and however we’re living our lives.

In this messy world, that’s not often easy. Our preacher this morning, the Most Rev. Hosam Rafa Naoum, archbishop of The Episcopal Diocese of Jerusalem, is well acquainted with the conflict endemic to Israel and Palestine. Just this week he issued a statement condemning Israel for breaching the door of one of his churches, St. Andrew’s in Ramallah, during a 3 a.m. raid on Al-Haq, a human rights organization that keeps an office there.

Israel calls it a terrorist organization. Nine European nations disagree. A colleague told me Israel dislikes Al-Haq for trying to bring Israeli soldiers and commanders before the International Criminal Court. As we talked after church, Hosam described his efforts to learn more and calm tensions. He said Al-Haq has had an office at St. Andrew’s since 1979, when it was co-founded by an Anglican.

It’s a point of pride for us but also a sign that things are continuing to spiral down for Palestinians. A great nation wants to be accountable for its misdeeds. A true democracy doesn’t put a yoke on the shoulders of human rights lawyers. It removes the yoke and puts them in the seat of honor.

Hosam’s sermon nevertheless brimmed with encouragement. We’d heard in Luke’s gospel how religious leaders criticized Jesus for violating Sabbath rules by healing a woman who’d been suffering from a crippling ailment for 18 years. If Jesus had had an office, they probably would have raided it.

Yet the archbishop finished by renewing Isaiah’s call for those acts of love, mercy, and sacrifice which beget God’s spirit of joy, peace, and abundant life. He even invoked the historic unity of the Semitic people of this region. The category includes both Jews and Arabs. Jews say shalom, Arabs salaam, he said, but both mean peace. They say it every day here. The next thing would be to do it.

Cafe on the Via Dolorosa

Holy land pilgrims guided by Qumri Pilgrimages will remember Willie, who run a busy cafe on the Via Dolorosa, near St. Anne’s Church. Iyad sits you down to take a breather with Willie’s delicious fresh-squeezed pomegranate juice. I asked for a cappuccino and sat and watched Willie and his colleagues deal graciously with about a dozen customers, including one from the U.S. who demanded seven bottles of water for the price of five. Dude didn’t look like he really needed to save the $1.50, but the guidebooks say barter, and so he did.