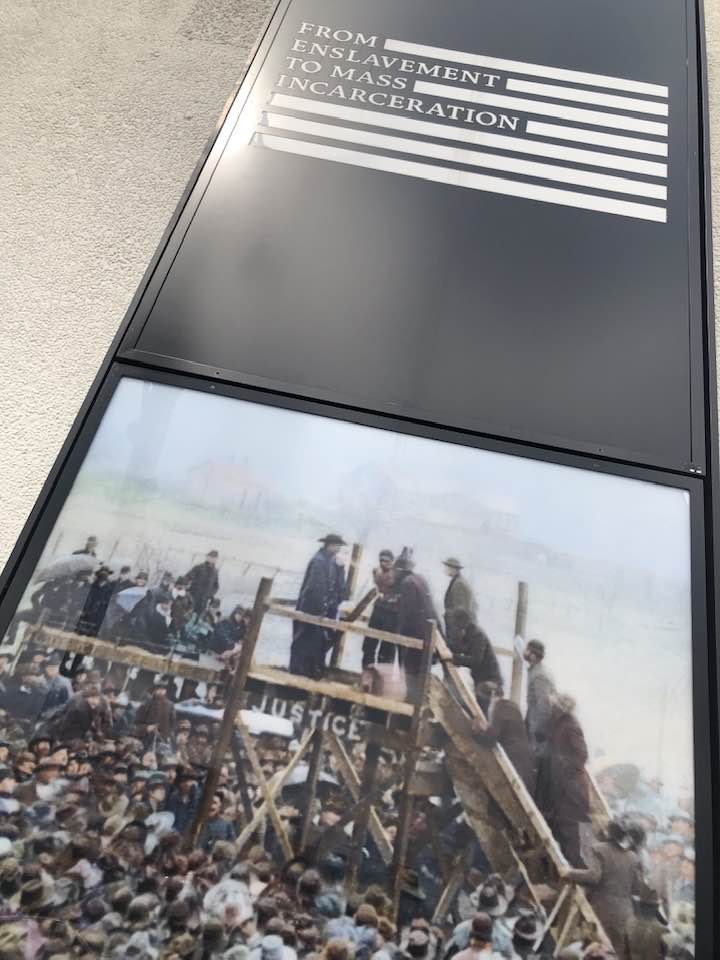

Like the prophets he quotes with ease, Bryan Stevenson, raised in the AME Church, embodies the irresistible moral authority of a singular vision of justice. On retreat through next Monday in Alabama, The Episcopal Church’s bishops spent today exploring two places in Montgomery of towering significance that wouldn’t exist without him. “The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration” draws a line connecting four dots: Slavery, our failed post-Civil War Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow, segregation, and mass incarceration. A mile away, The National Memorial for Peace and Justice memorializes 4,400 people of African descent murdered in what Bryan calls racial terror lynchings.

Like the prophets he quotes with ease, Bryan Stevenson, raised in the AME Church, embodies the irresistible moral authority of a singular vision of justice. On retreat through next Monday in Alabama, The Episcopal Church’s bishops spent today exploring two places in Montgomery of towering significance that wouldn’t exist without him. “The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration” draws a line connecting four dots: Slavery, our failed post-Civil War Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow, segregation, and mass incarceration. A mile away, The National Memorial for Peace and Justice memorializes 4,400 people of African descent murdered in what Bryan calls racial terror lynchings.

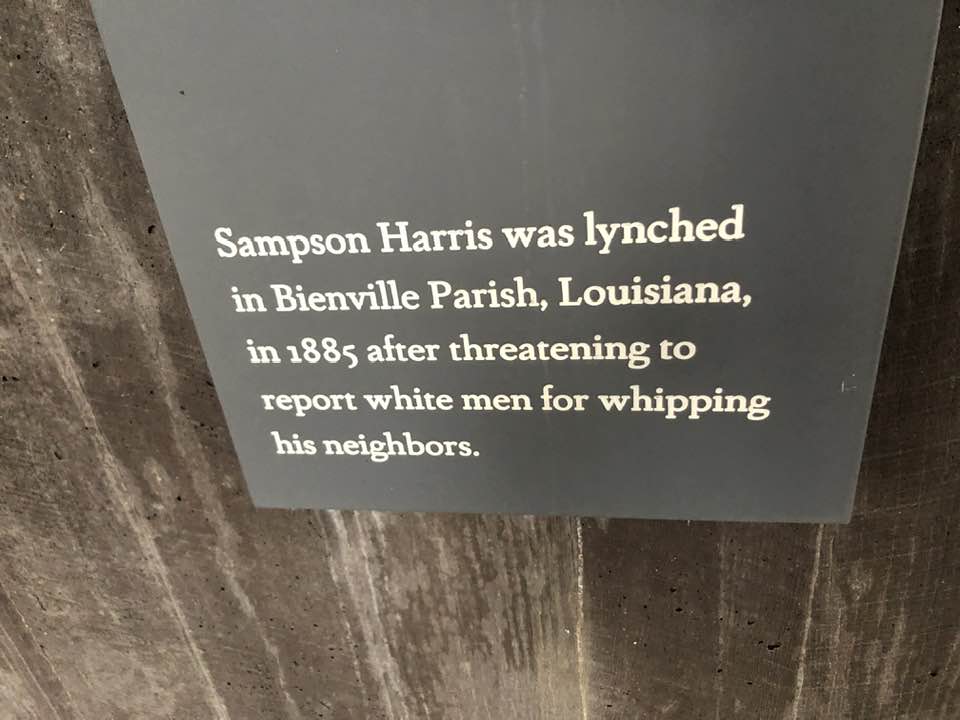

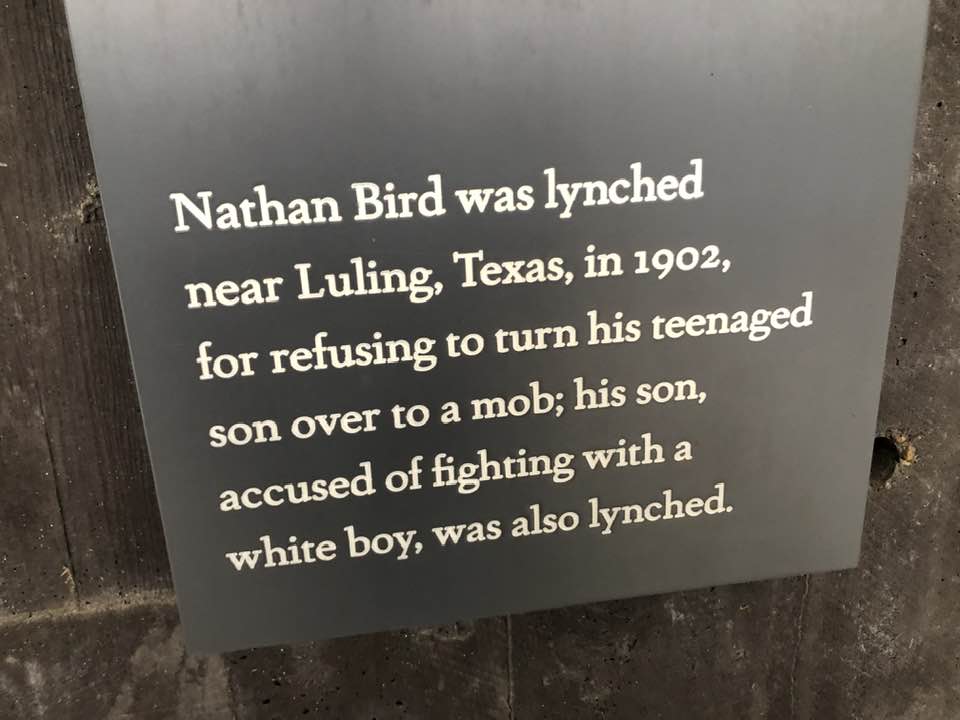

The museum’s narrative is merciless, like the evils it depicts. The hatred and animalistic rage absorbed by victims of slavery and racism across the centuries left me feeling astonished and ashamed. There’s relatively little about the civil rights movement. Bryan’s and the curators’ focus on mass incarceration precludes a happy ending. Nearly a third of men of African descent in their twenties are in prison, on probation, or in prison, many charged with drug crimes. Whites do as much if not more drugs than Blacks, but the latter get charged and jailed more. Half of federal prisoners were convicted of possession. They should get medical treatment instead, all habitual drug users should, but our society hasn’t figured that out yet — because, Bryan would say, we are still the thrall of the 400-year-old myth of white superiority. As the exhibits point out, my old boss Mr. Nixon had a hand in this, with his war on drugs and law-and-order campaigning.

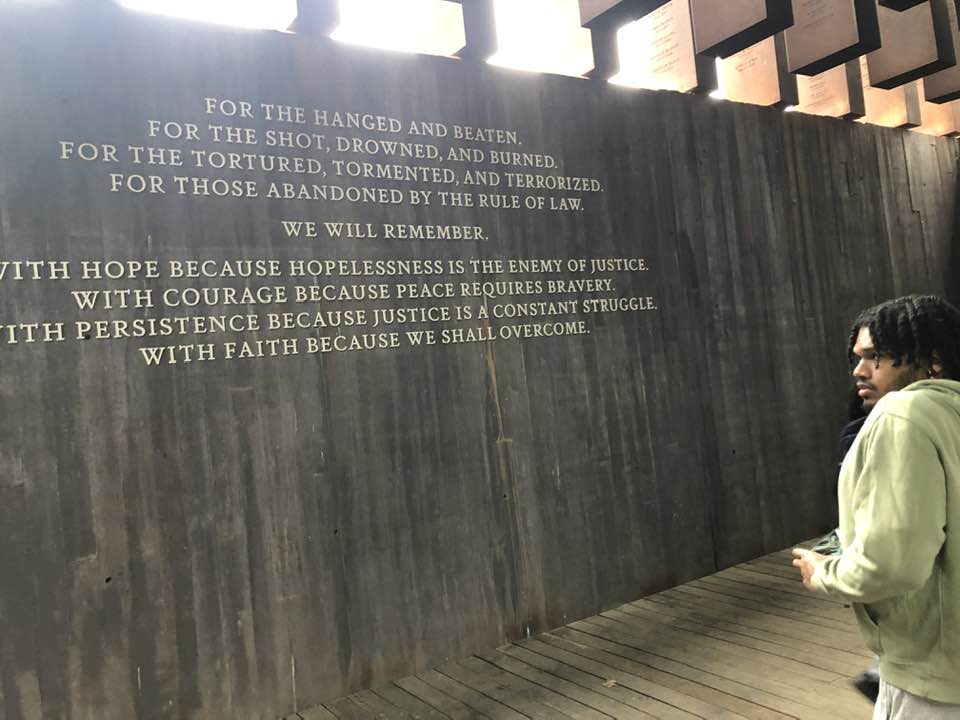

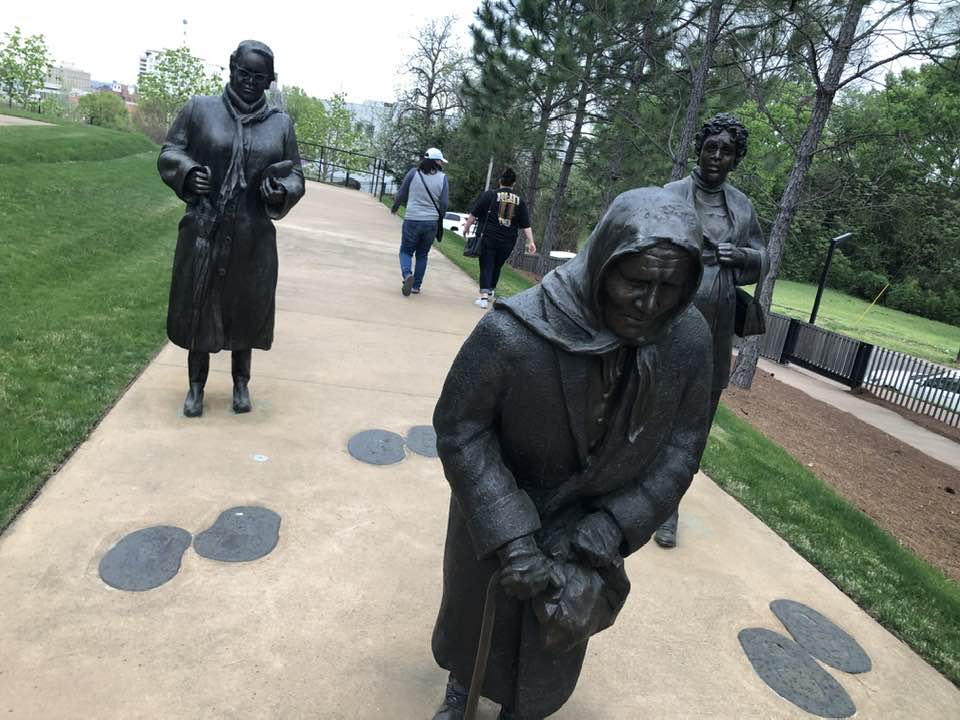

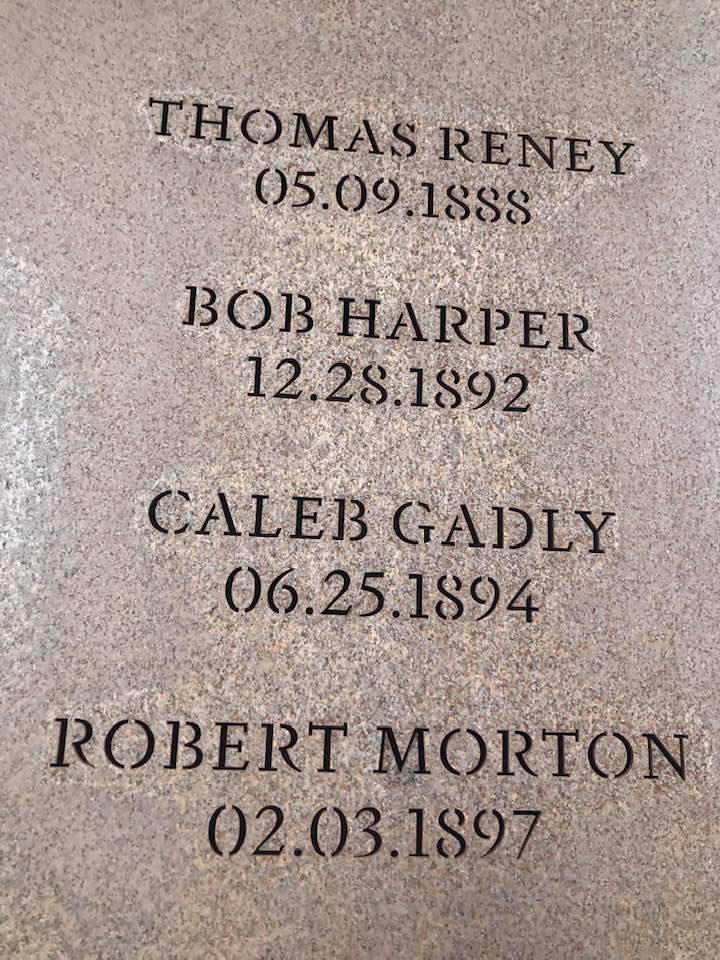

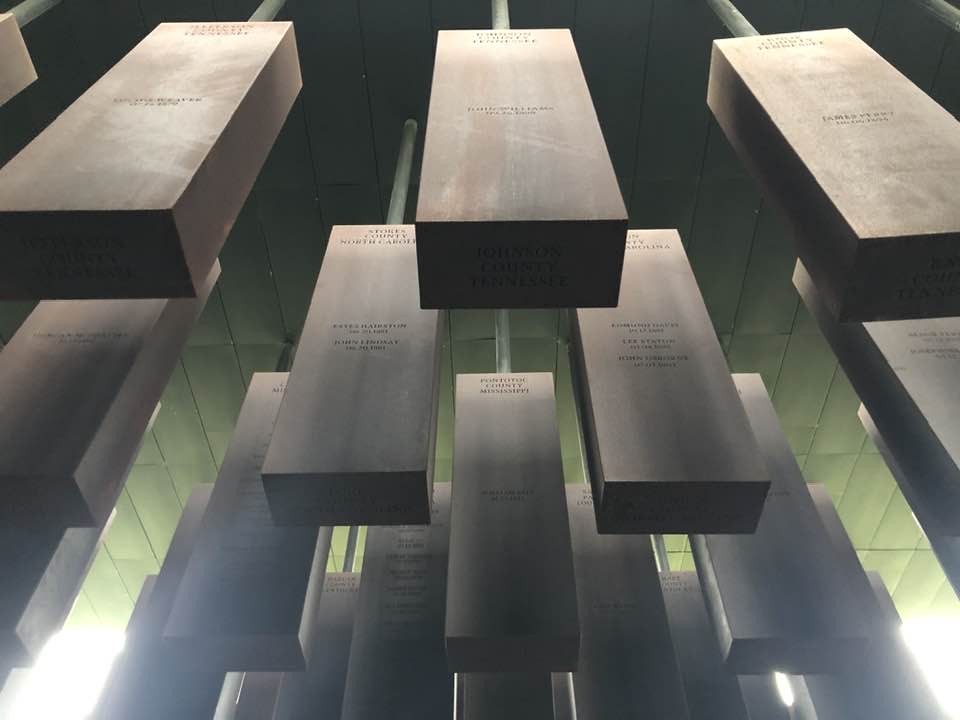

One wishes one of our presidents or Congress had thought to build the four-acre memorial to lynching victims at the center of Washington, D.C. But that would have taken prophetic focus. So Bryan and his team opened it in 2018, at the same time as the museum. Suspended from the ceiling, 800 steel columns bear the name of the documented victims, organized county by county. It was moving to see bishops praying over the columns from their states or quietly repeating the names. The further you go in the memorial, the higher the columns are. You get a chill when you realize they’re hanging. Untold thousands more names are lost to history, although not to God. Organizers made an extra column for each county. Officials are waiting for the counties’ officials to come pick them up and display them locally. Some have, evidently, but most have not. They are sitting there, waiting for prophetic focus at the county level.

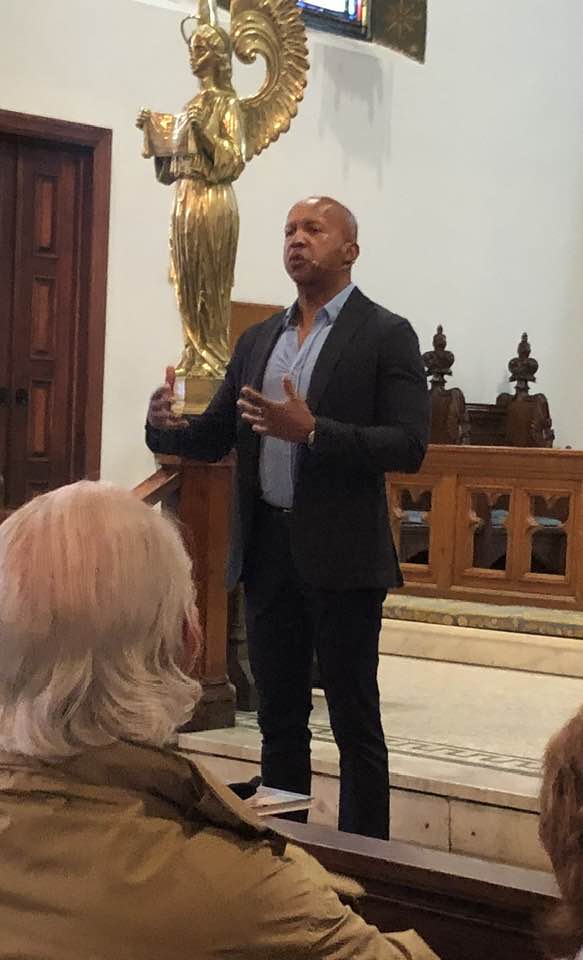

We had lunch at St. John’s Episcopal Church (Montgomery, Alabama), where our host, the Rt. Rev. Glenda Curry of Alabama, once served as rector. A lay leader presented the church’s history, including the removal of the pew where Jefferson Davis is thought to have sat with his wife during the four months in 1861 that the secessionists headquartered in Montgomery. And then we heard from Bryan himself — a Harvard-trained lawyer who has argued twice before SCOTUS, author of the popular memoir Just Mercy, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, devoted advocate of those unjustly accused and imprisoned, opponent of the death penalty. He is a kind of a miracle. He called us to be part of the process of truth telling and reparation, in the church and society, that he said is the only way to heal our 400-year-old wound.