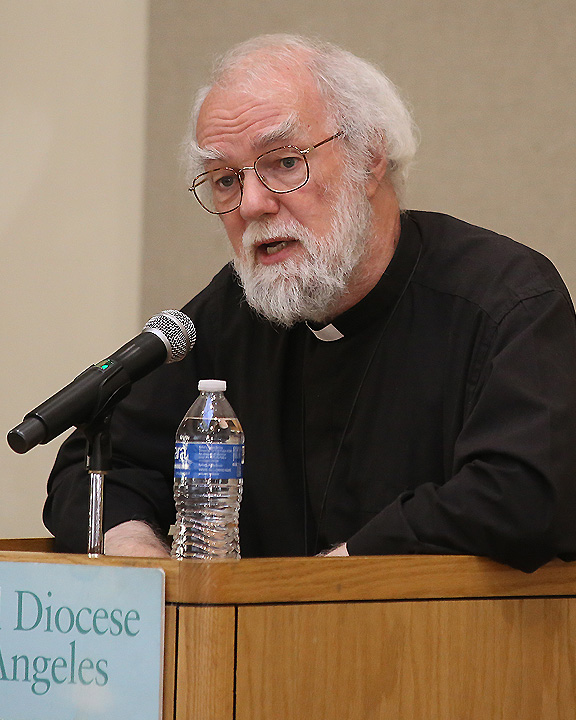

Former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams listens to a question at a Sept. 24 clergy day at the Cathedral Center of St. Paul. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

ADDRESSING CHALLENGES within the Anglican “family” is less about problem-solving and more about creating opportunities for mutual gratitude, connection and understanding, former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams told a Sept. 24 gathering of clergy and laity in Los Angeles.

“I am saying ‘Anglican family’ rather than ‘Anglican Communion’ because we’re a very fractured communion but we’re still family – like so many families, quarreling till the cows come home,” he said. “What gives us our family solidarity is, of course, that dependence on God’s call, God’s welcome.

Archbishop Rowan Williams addresses a gathering of clergy on Sept. 24 at the Cathedral Center. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

“We are, at the moment, in the middle of a period of colossal uncertainty in the life of our Anglican family,” he told the gathering of about 150 people at the Cathedral Center of St. Paul in Echo Park. “There is uncertainty, division, a measure of suspicion still and a sense that our conventional and inherited ways of being Anglicans together across the world have come under almost unmanageable strain.”

Los Angeles Bishop John Harvey Taylor welcomed Williams, whose Sept. 22 – 26 visit to the Diocese of Los Angeles also included presiding at the 100th anniversary celebration of the Parish of St. Mary in Palms (see story here), and a visit with students and staff at St. Margaret of Scotland Episcopal Church and School in San Juan Capistrano.

Taylor said Williams initially came as part of the centennial celebration “because he had known [St. Mary’s rector] the Rev. Vincent Shamo when he was a priest serving in his native Ghana.” In addition, Williams has a close academic partnership with Deborah Shuger, a UCLA medievalist who serves as a senior warden at St. Mary’s.

Williams agreed to stay longer and “spent time with us to do a soft launch of our capital campaign with potential contributors and supporters,” Taylor said. “He will visit St. Margaret’s and help them feel a bit more closely connected with the worldwide Anglican Communion. He is excited to spend this time with all of you.”

The Very Rev. Canon Ian Davies, rector of St. Thomas the Apostle Church in Hollywood, dean of Deanery 3 and a longstanding friend of the former archbishop, introduced Williams to the gathering.

The enthusiastic audience laughed when Davies commented that Williams “had once been arrested outside an American Air Force Base for singing psalms in East Anglia.

“He is fluent in nine or ten languages, including Russian and Welsh and, by my last count had 19 honorary doctorates. By now, there may be more,” Davies said. “He regularly visits with the royal family and brings such devotion and grace and holiness incarnate by his very words and wisdom.”

Rowan Williams preaches at Eucharist during a Sept. 24 clergy day in the Diocese of Los Angeles. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

Challenges: context, awareness, mutual understanding

While acknowledging that as the 104th archbishop he had to make “uncomfortable adjustments at both ends of the spectrum, liberal and conservative, north and south” to keep everyone at the table, Williams said he believes a problem-solving-by-committee approach no longer effectively addresses current challenges.

Traditional unifying elements within the communion, like the Anglican Consultative Council; the Lambeth Conference, the every-ten-years gathering of bishops; and the Primate’s Meeting of presiding bishops, originally intended for mutual support and counsel, over time shifted into problem-solving mode.

Rowan Williams engages with several clergy on Sept. 24 during his visit to the Diocese of Los Angeles. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

“That is one reason why in 2008 I decided we would not have resolutions at the Lambeth Conference,” Williams said, “simply to take our minds away from an obsession with trying to solve problems and instead to see what we could do to build relationships, to come together to consult, to pray, to support.”

Other contributing factors include fragmented theological education, and a huge range of global social, political and cultural tensions and shifts, which have localized into “a kind of ongoing standoff” within various provinces of the Anglican Church over the marriage, ordination and full inclusion rights of LGBTQ persons.

For example, he said, the expansion of inflexible Pentecostal Christianity in parts of Latin America and Africa and the resurgence of Islamic extremism in Sudan, Nigeria and Uganda, as well as sometimes bloody conflicts between the Christian and Muslim community have resulted in “a sense which a good many of our Anglican brothers and sisters feel that they are being measured by standards of other communities. When they feel their witness is in some way being compromised by Anglicans elsewhere in the world, they feel it acutely,” Williams said.

“Which will make people in Nigeria, Tanzania and Sudan say, ‘we are regarded as weak in all sorts of ways — doctrine, ethics, polity and governance,’ as opposed to the great strength of the uncompromising witness both of Pentecostal Christians and Muslims — and that’s a bit of a problem that’s become more and more acute as the years have gone by.”

Archbishop Williams pauses to bless Lauren, daughter of the Rev. Laurel Johnston. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

Elsewhere, such as the United States, Europe, Ireland and Scotland, many are seeking out Anglicanism as a way to retain liturgical and sacramental richness but escape “the inflexibility of and inhumane moral rules and social conventions” of some other traditions, he said. And while Anglicanism is attractive in some parts of Latin America, it doesn’t necessarily work the same way in regard to ethical questions.

“There needs to be a bit of binocular vision across the world to see the very different ways in which these political dynamics work themselves out,” he said.

“Maybe we should just acknowledge that we are in a transitional period and that that limits what we can do; that there is not a magic bullet to this,” Williams said. “We need to look very, very, carefully and imaginatively at where it is that mutual understanding really comes alive.”

United in mutual aid: Anglican Alliance; Mother’s Union

International development, relief and advocacy agencies, such as the Anglican Alliance and the Mother’s Union, are examples of groups in which a number of provinces participate “who won’t cooperate about anything else or in any other context,” Williams said. “As if there still is something about the bare human need of the Gospel response which remains recognizable, even when you’re quarreling about almost everything else.

“The Mother’s Union, as it exists in many of our provinces, is a much more important cement of unity in the communion than the primates’ meeting,” he said. “It is the largest lay fellowship in the Anglican family and does incalculable work in binding together people across different cultures and environments.”

“We need to ask how we do more in that sort of way, building those relationships between active and committed lay people, not just hierarchs and committees across the communion.”

Rowan Williams, assisted by Fernando Valdes, blesses the cathedra, or bishop’s chair. It will soon be moved to St. John’s Cathedral after a 25-year sojourn in the Cathedral Center, which will be re-christened as St. Paul’s Commons Oct. 22 (see story on the Episcopal News homepage). Photo: Bob Williams

The Indigenous People’s Network and the consultation on theological education are also examples of creating much-needed space for recognition and gratitude, he said.

“The question in any deep division in the Christian church is; how do we recognize one another as disciples? Because breakthrough comes when you look at someone else’s face and see that, at least in some respect, it is turned toward the same God you seek to turn to.

“And that is when another round of engagement becomes possible,” he said. “Not a resolution but a level of patience or even gratitude for one another. I believe that that kind of mutual Christian recognition is very profoundly tied up with our willingness to be grateful for one another.”

In that way, gratitude becomes evangelistic, he said.

“The spectacle of a church vigorously tearing itself apart over just how exclusive it can afford to be is not one that makes the world feel grateful, oddly enough,” he said amid laughter. But, he added, “The spectacle of a church divided but faithful; that does give the world something to be grateful about.

“And those difficult elusive moments when we can show something of that mutual gratitude across division, those evangelistic moments are very precious in a culture where … everybody seems to be running for the corners of the room.”

It may mean risk-taking.

Assisted by Fernando Valdes, Archbishop Rowan Williams sprinkles holy water on the historic bishop suffragan’s chair that will soon be moved to St. John’s Cathedral in Los Angeles. At right, Bishop Suffragan Diane Jardine Bruce, Bishop John Harvey Taylor and Provost Frank Alton of St. Athanasius Church look on. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

Like “those from the Episcopal Church who have continued, sometimes in very difficult circumstances, to travel to South Sudan to maintain educational and development work” while the local diocese is pressured to resist their help.

Or those who spent time in Rwanda, Tanzania, “simply building recognition, simply creating environments in which it is possible to see that face turned toward Christ in one another.”

It may involve becoming “conscientious objectors to the culture wars,” like Los Angeles Bishop Assisting Sammy Azariah, who as primate of the Church of Pakistan, sought to build bridges across cultures and faiths, “building personal, face-to-face recognizability,” he said.

While in transition, “we can’t know what the unity of the Anglican family will look like 50 years down the road,” he said. “It is not given to us to know the future. But it is demanded of us that we be faithful today. Faithfulness today requires … trying to get closer to the heart of what we mean by the Body of Christ.”

Williams added: “What interests me again and again in the life of our Communion is not so much what we do to get institutional conformity and harmony, but what we do to witness to the fact that the church of God does not exist because we decide. It exists because of God’s invitation.”

“Sooner or later we’re going to have to come to terms with those other people God has invited. Whether we identify ourselves as traditionalist or liberal … the rest of them are not going to go away.”

Williams posed for photos and selfies with many of the clergy attending the Sept. 24 event at the Cathedral Center. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

Williams blesses a cross for a clergy member. Photo: Janet Kawamoto